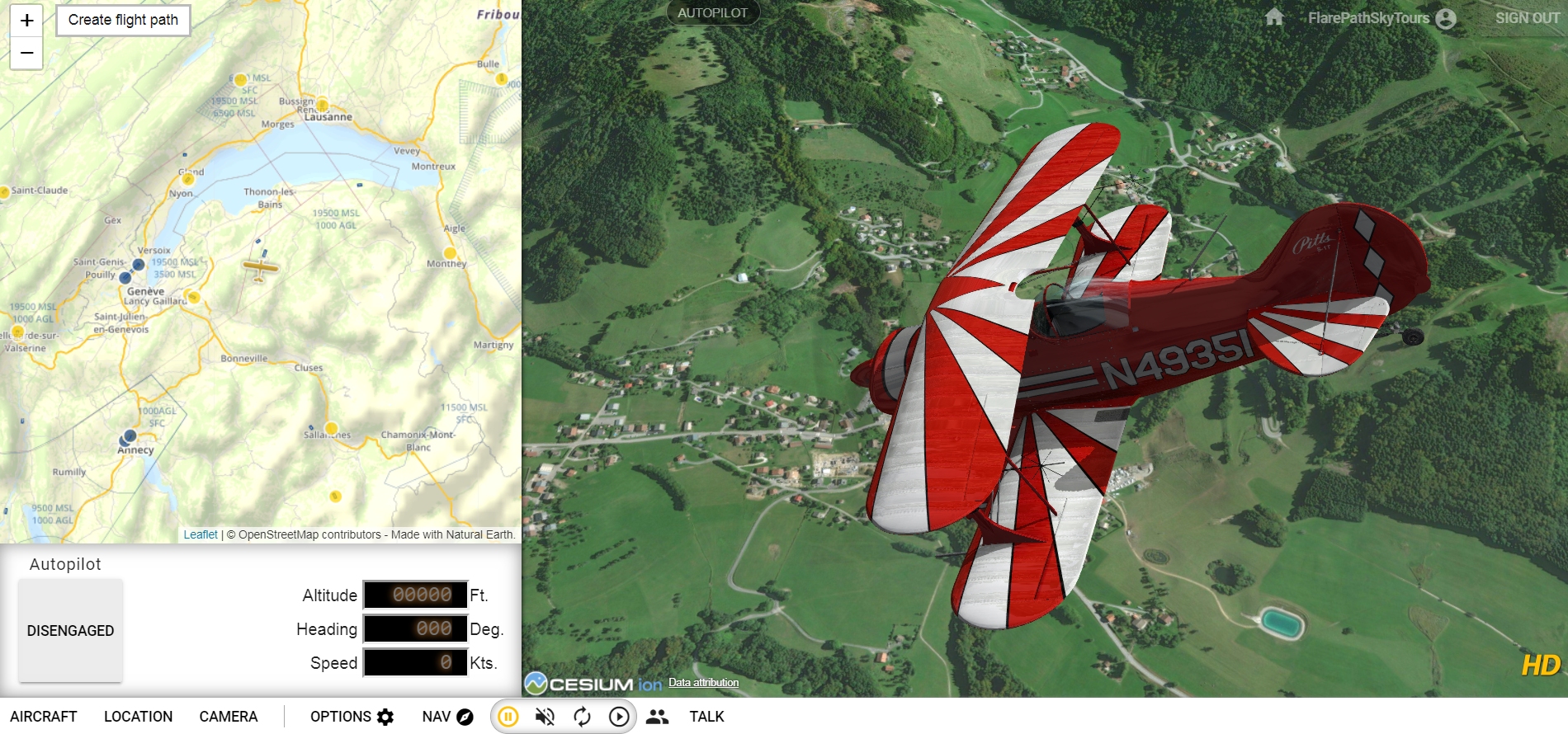

Why GeoFS? Technical issues mean FSX and X-Plane are not an option for the cash-strapped FPST at present. While Xavier Tassin’s creation has little to offer the armchair aeronaut after accurate avionics, sophisticated weather modelling or eye-catching 3D architecture, enhanced with streamed HD terrain textures (yours for a 10 Euro annual fee) as a vehicle for fuss-free aerial sightseeing it’s far from shabby.

Why the Isle of Wight? Three reasons. 1) Ever since my trusty co-pilot, Roman, stumbled upon a century-old guidebook devoted to the place in a box of books donated to the Flare Path reading room, he’s been wanting to pay it a visit. 2) A full fuel tank wasn’t included in the Flybe deal so our maximum range today is somewhat limited. 3) Shameless self-indulgence; one of my earliest holiday memories features me wading Gulliver-like around a cement facsimile of the Island. Everyone safely strapped in? Great. Let’s roll…

…over tarmac that hid an elongated explosive secret for sixty-odd years. During remedial work on Solent Airport’s runway in 2006, workmen discovered a subterranean pipe bomb sixty feet in length. Designed to render the coastal airfield, then known as HMS Daedalus, unserviceable in the event of a German invasion, the charge was one of twenty planted under the Portsmouth-adjacent strip. Before we strike out across the Solent for an arcadia Roman’s guidebook describes thus: “As a resort of those who make holiday, the Isle of Wight is an embarrassment. Its attractions are so numerous and diverse that the visitor pauses on the shore to weigh the merits of half-a-dozen famous spots. Shall he remain in Ryde, seek the sands of Sandown, the green recesses of Shanklin, the bold heights of Ventnor, or, rejecting all of these, push on into the less well-known western places where the railway whistle has only recently been heard? As a matter of fact, there is small need for such precision. The visitor to the Isle of Wight may drop down anywhere along the shore or inland, and be certain that the spot shall be a garden, and not a wilderness. He will find on every hand scenes of beauty such as, within the same compass, no other place frequented by tourists can show.”

…let’s briefly orbit a museum on the airport’s southern fringe that counts amongst its exhibits two* of the most extraordinary vehicles ever to shadow the seabed. Those 56m-long krakens down there are retired SR.N4 hovercraft. Capable of an impressive 83 knots in calm conditions and capacious enough to transport sixty cars and their passengers, the type plied the Channel between 1968 and 2000. Until the arrival of the Pomorniks, they were the world’s largest hovercraft. *Today, only one of the Hovercraft Museum’s SR.N4 remains. To make space for other exhibits, Princess Margaret was scrapped last March

Now we’ve gained a little altitude the Island’s distinctive outline starts to become discernible. I’ve always thought of our destination as being diamond-shaped. My colleague’s Edwardian Lonely Planet guide sees things a little differently: “The Island is of irregular rhomboidal form, contracting at the two extremities - especially at the west – and has been frequently said to resemble a turbot”

Should my fuel calculations prove inaccurate, the return crossing of the Solent - seven kilometres wide at this point - may involve Sailaway or Ship Simulator 2008. The old VSTEP sim and its sequel included recreations of two hardworking local vessels, Red Eagle and Red Jet 4, together with a visually pleasing depiction of this slice of the central Solent. All that was missing was simulation of the powerful tidal streams that surge through the strait.

Rather than making landfall at Cowes, the cleft in the turbot’s dorsal fin, I’ve chosen this secluded beach two kilometres to the east. If paparazzi had existed in the Nineteenth Century, this would have been one of their favourite haunts. It was here that Queen Victoria and family used to sea-bathe while staying at Osborne House, their nearby palazzo. Vicky’s restored bathing machine stands just over there, on one of its pegs the “Kiss me quick” hat she would often wear when building sand Windsor Castles, or slathering Albert’s back with Factor 15.

The next place of interest on our clockwise Wight flight is a six-sided field close to Wootton Creek. For a few days in late August, 1969, that patch of pasture was no place for field mice, grasshoppers, or toilet anxiety sufferers. The venue for the second of the Island’s three original music festivals, the lucky 150,000 who gathered there witnessed, amongst other things, a famous Bob Dylan performance.

Little seen in public since a motorcycle prang three years earlier, Dylan, looking discordantly dapper in a cream suit, performed a 17-number country-tinged set mainly composed of material from Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, John Wesley Harding, and Nashville Skyline. The fact that Roman (born 1972) isn’t visible in any of the crowd footage of the event, suggests his experiments in dendrochronographic displacement will never come to anything.

Given short shrift by our Ward Lock, ’new’ Quarr Abbey, the striking brick confection currently conspicuous under Tarka’s starboard wing, is - according to British architectural connoisseur Nikolaus Pevsner - “among the most daring and successful church buildings of the early 20th century in England" and boasts “without any doubt, the finest interior of any building on the Island.” I’d ask Roman to buzz the impressive Moorish tower (monk-architect Paul Bellot was heavily influenced by his travels in Spain) if all such edifices weren’t as flat as communion wafers in GeoFS.

Ryde, our next port of call, has much to offer the transport enthusiast. The town’s prominent pier has changed relatively little since the writer of our 1916 travel tome described it as “hydra-headed”. Although the trams that ran along its length vanished in 1969, ferries from Portsmouth and trains from the Island’s south coast still exchange passengers at its splayed tip.

More than eighty years old, the trains in question - Class 483s - spent half a century beetling through London’s bowels before emigrating to the Island in 1988. An unusually low tunnel between Ryde Esplanade and Ryde St. Johns Road (alight here for the town’s excellent bus museum!) explains the Island Line’s fifty-three year association with ex-London Underground electric multiple units. Due for replacement in March, the 483s and their Hampshire habitat were digitised by the company now known as Dovetail back in 2009.

On the slipway next to the pier sit two extremely rare amphibians. Solent Flyer and Island Flyer are passenger carrying hovercraft resting between runs to Southsea. Unique in Europe and with very few equivalents further afield, the 78-seat Griffon Hoverwork machines can dart across the strait in less than ten minutes. The WightLink catamarans that use the nearby pier, seem positively ponderous in comparison, taking twenty-two minutes per crossing.

On their way to and from the mainland, Hovertravel’s cushion craft pass close to a spot where a sizeable British warship foundered in improbable circumstances. No, I’m not referring to the Mary Rose (although the site of her sinking is also currently in view). The ship I’m thinking of is the HMS Royal George, a 100-gun Battle of Cape St. Vincent veteran that went down with heavy loss of life off Southsea in 1782.

No storm, rocks, or Frenchmen were involved in the catastrophe. Prior to setting sail for Gibraltar, the Royal George’s hull was undergoing cleaning - a process that involved heeling over the ship by shifting its guns. The operation was ineptly managed. Tilted too far, the sea rushed into her port side gun ports with predictable results. Around 900 souls, including approximately 300 women and 60 children (family members seeing their husbands, fathers, and sons off) perished, many of the corpses washing up at Ryde.

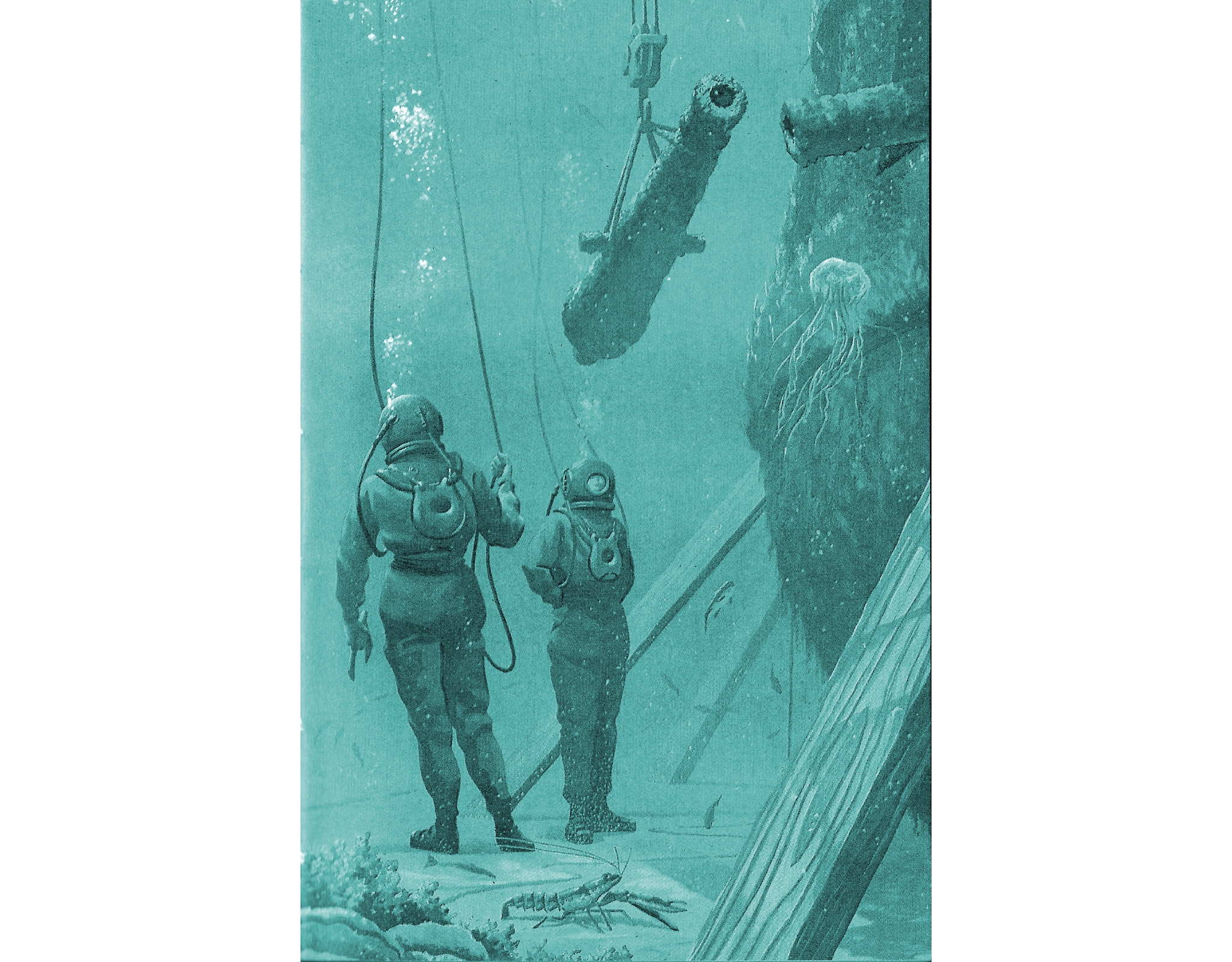

Sitting upright in relatively shallow water near the mouth of Portsmouth Harbour, the Royal George proved a headache for the Royal Navy for sixty years. Several attempts to raise her with slings failed. It wasn’t until underwater salvage pioneers, the Deane Brothers, came on the scene with their revolutionary air-fed diving helmet (later improved and incorporated into a suit by their acquaintance, Augustus Siebe) that progress was made. The lead-sheathed barrels of gunpowder that obliterated the last remnants of the hazard in 1840 were planted by divers from the Royal Engineers wearing the first examples of the now familiar “standard diving dress”.

Two of the attractions that brought visitors to Seaview, the next sizeable settlement on our itinerary after Ryde, in 1916 are long gone. “The constant procession of warships, liners, and craft of all kinds” that was “a source of never-failing interest” to tourists a hundred years ago has thinned out considerably, and the “handsome” chain pier built in 1881 was finished off by storms in the early 1950s. Hang a right here, Roman, and make for Bembridge. Judging by the unusually double-edged entry in the Ward Lock guide, its writer spent a very dull evening in this village, and may have encountered the odd stale bun and malodorous earth closet during his stay: “The scenery is not sublime; the smaller shops are still rather primitive; and we are not even sure that the older cottages conform to the very latest requirements of civilisation. But if you care for a place where the only noise is the laughter of children, where the only daylight occupations are yachting, golfing, bathing, and fishing, and the evening occupations as nearly as possible nil; where the only excitement of the day is the arrival of a railway train, or the departure of a diminutive steamer, then Bembridge is not likely to disappoint”.

Although Bembridge saw its last train in 1953, it’s not the transport backwater it appears to be on first inspection. Britten-Norman, the company that gave the world the Islander (a plane not dissimilar in concept and configuration to Tarka), Trislander and Defender is a multinational concern today, but was born and remains headquartered at the small airfield over yonder (Most of the firm’s airfield operations moved to Solent Airport – our starting point – in 2010). The Islander’s maiden flight was from Bembridge in June 1965.

Thanks to the Francophobia rampant in Downing Street in the mid Nineteenth Century, the Island gained a rash of impressive fortifications in the 1860s. We’re well placed to inspect one of these at the moment. Bembridge Fort, like the rest of Palmerston’s follies, was swiftly rendered irrelevant by technological advancements and events across the Channel. Its 7-inch RBL Armstrong guns never fired a shot in anger. The Fort probably engaged its first foe during WW2 when an anti-aircraft batteries stationed within it harried the Lufwaffe formations making for Portsmouth, Southampton and Cowes.

Time to hand out the complimentary bags of “Dino Bones” (Mini Twiglets artfully rebranded with a marker pen yesterday evening). In addition to being just one letter away from a frightening FRPG quest destination, the Isle of Wight is also a palaeontologist’s paradise – one of the richest sources of dinosaur fossils in Europe. Remains of some genera such as Caulkicephalus (a toothy fish-partial pterosaur) and Hypsilophodon (an agile dog-sized herbivore) have been found here and nowhere else. The only known fragment of Yaverlandia bitholus, a tiny bird-like biped, was found close to our next waypoint, the village of Yaverland.

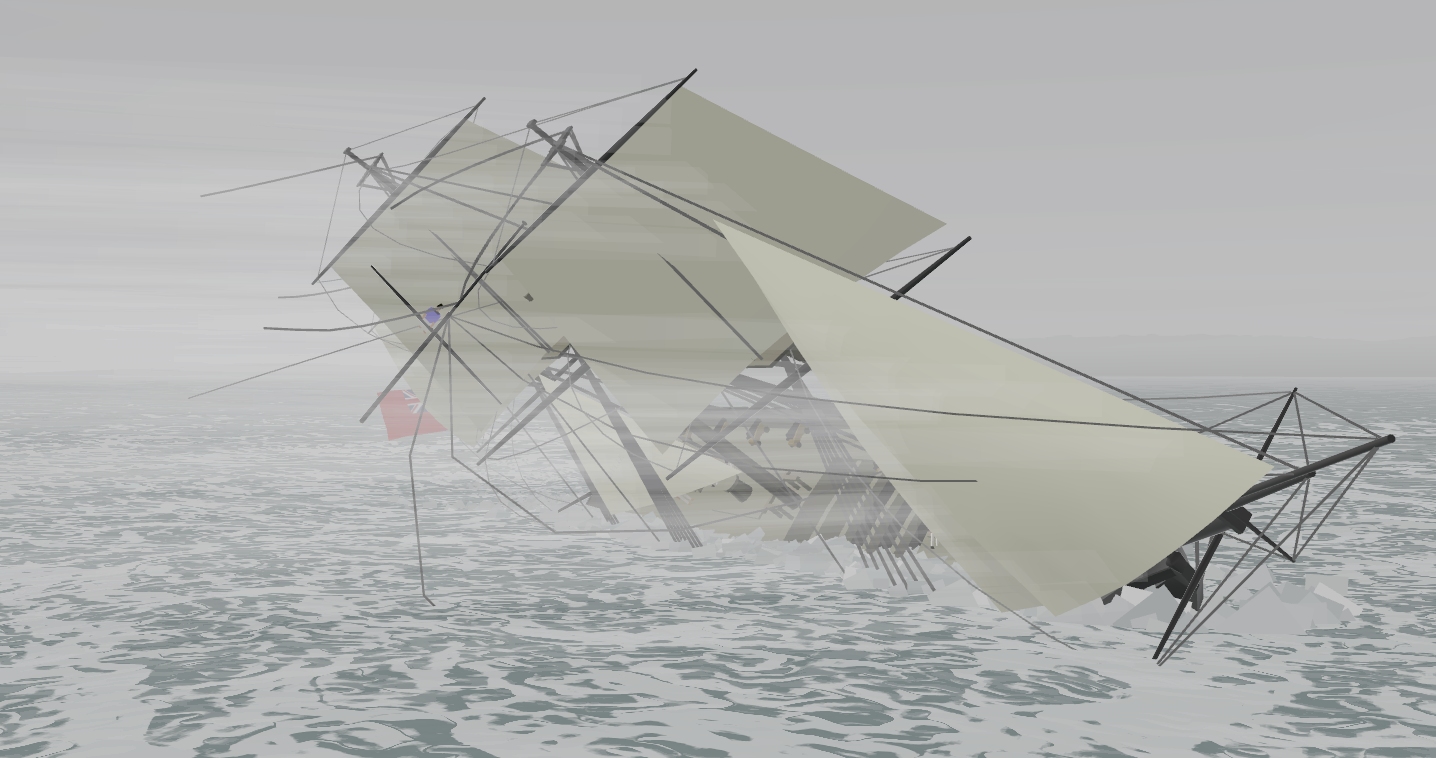

Is it too soon for another harrowing shipwreck tale? On March 24, 1878, HMS Eurydice, a 26-gun Royal Navy corvette returning to Portsmouth after a three-month tour of the West Indies, foundered out there in Sandown Bay, the victim of a meteorological mugging. Out of a deceptively blue Spring sky a towering black snow squall partially hidden from view by the high ridge of Ventnor Downs (see on) pounced on the ship from the north as it cut across the bay under full sail. The officers and crew, possibly worse for wear after premature homecoming celebrations, realised the danger much too late. Eurydice was forced over onto her starboard beam-ends by the ferocious onslaught of wind and wet snow. The upper portions of the fore and mizzen masts were ripped away, and the chilly sea began to pour in through open ports. Of the 319 men and boys aboard, only two were saved.

The disaster, witnessed by, amongst others, a young Winston Churchill, spawned a ghost if you believe F. Lipscomb, an RN sub commander in the 1930s, and Prince Edward, the current Earl of Wessex. Both men claim to have seen a spectral version of the corvette close to where she went down. Lipscomb was so convinced by the apparition he ordered evasive action to prevent a collision.

Blessed with the Island’s best beach, Sandown has hosted some notable holidaymakers over the years. Charles Darwin, Lewis Carroll, Richard Strauss, George Eliot, and Queen Victoria’s son-in-law, Frederick III have all strolled along that prom*. See that souvenir shop at the shore end of the pier? Like George Eliot, I bought my very first Commando comic there. *Where the brass bands played, tiddely-om-pom-pom Sandown bleeds into unremarkable Lake which, in turn, bleeds into leafy, cliff-perched Shanklin, a destination the Ward Lock heaps praise upon… “Go where you will, you will find few prettier towns, none more happily situated… There is no cool green corner in the Island like Shanklin… It’s a town full of tasteful erections that the eye dwells on with pleasure.” Apologies for the “turbulence” ladies and gentlemen. I think I better take the controls for a spell - I’d forgotten just how juvenile Roman’s sense of humour was.

One of Shankin’s prettiest nooks, the damp ravine known as the Chine (You’re fired, Roman), has been the lair of a giant steel worm for the past 75 years. PLUTO, the trans-Channel petrol pipeline that kept the Allies’ vehicles moving as they pushed for Berlin, slithered into the sea here (later, a second pipeline was built at Dungeness). The network become operational too late to contribute to the Normandy breakout, but had carried over 172 million gallons of fuel to the continent by the war’s end. Several of the buildings constructed to disguise the area’s sixteen pumping stations still stand. In 1944-45 this pumphouse near the front at Sandown claimed to be an ice cream parlour.

The climb out of Shanklin ends on the breezy, gorse shawled heights of Ventnor Downs. Chances are, if you’ve visited the Isle in a video game before, this was the spot you came to. On August 16, 1940, the larks and stonechats hereabouts found themselves sharing sky with crook-winged Stukas intent on devastation. The Luftwaffe dive bombers had come to finish a job started four days earlier by Ju 88s.

They succeeded, disabling the radar station that sat on this ridge, but it was to be one of the Ju 87’s last achievements in the Battle of Britain. Two days later, facing eye-watering Stuka losses, Goering decided that the type would fly no more over England.

Splendid. It seems Ventnor, the town below the cratered upland, still has its magic paddling pool. Tots can still play at being titans, circumnavigating the Isle of Wight in the time it takes to devour an ice cream or manufacture a memory vivid enough to last a lifetime. Overtaken by time’s swift arrow and fatigue, I regret to say our own circumnavigation must halt here, at the turbot’s ventral fin, for the time being at least. Join me, probably next week, for the concluding part of this planet-friendly PC-powered peregrination.

(Click here for Part II)

This way to the foxer