I wish life were less complicated. Yeah, Orson Scott Card co-wrote it. Let’s just deal with that up front. I think that Orson Scott Card holds abhorrent views. I think he sounds like an absolutely dreadful person to be near. I wonder how many of the issues that run through The Dig’s plot are as a result of his concerning views. Who knows. My ideal version of events is the inestimable Sean Clark wrote all the brilliant stuff - of which there is so much - and Card did the crappy bits. Let’s pretend that’s true.

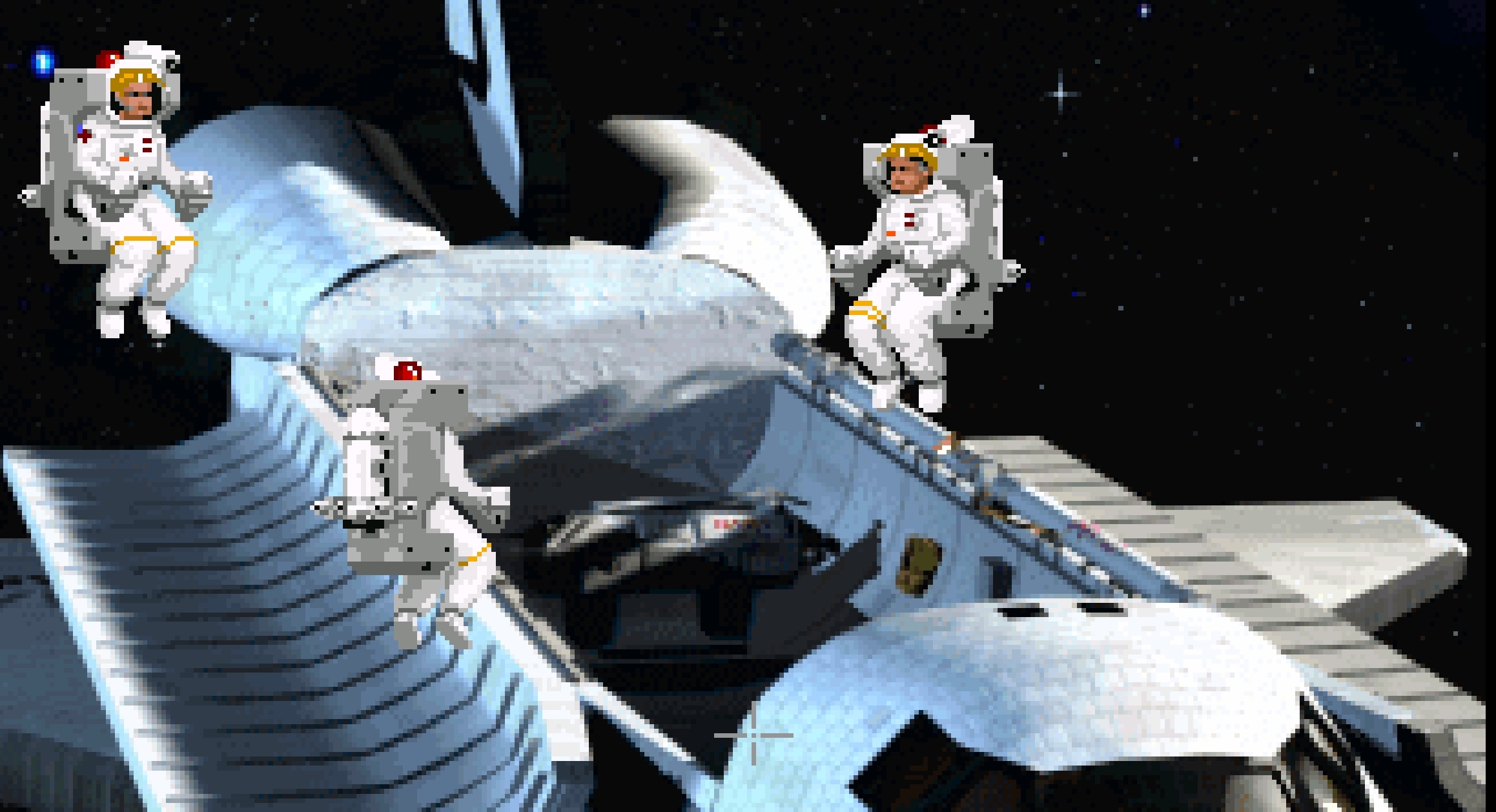

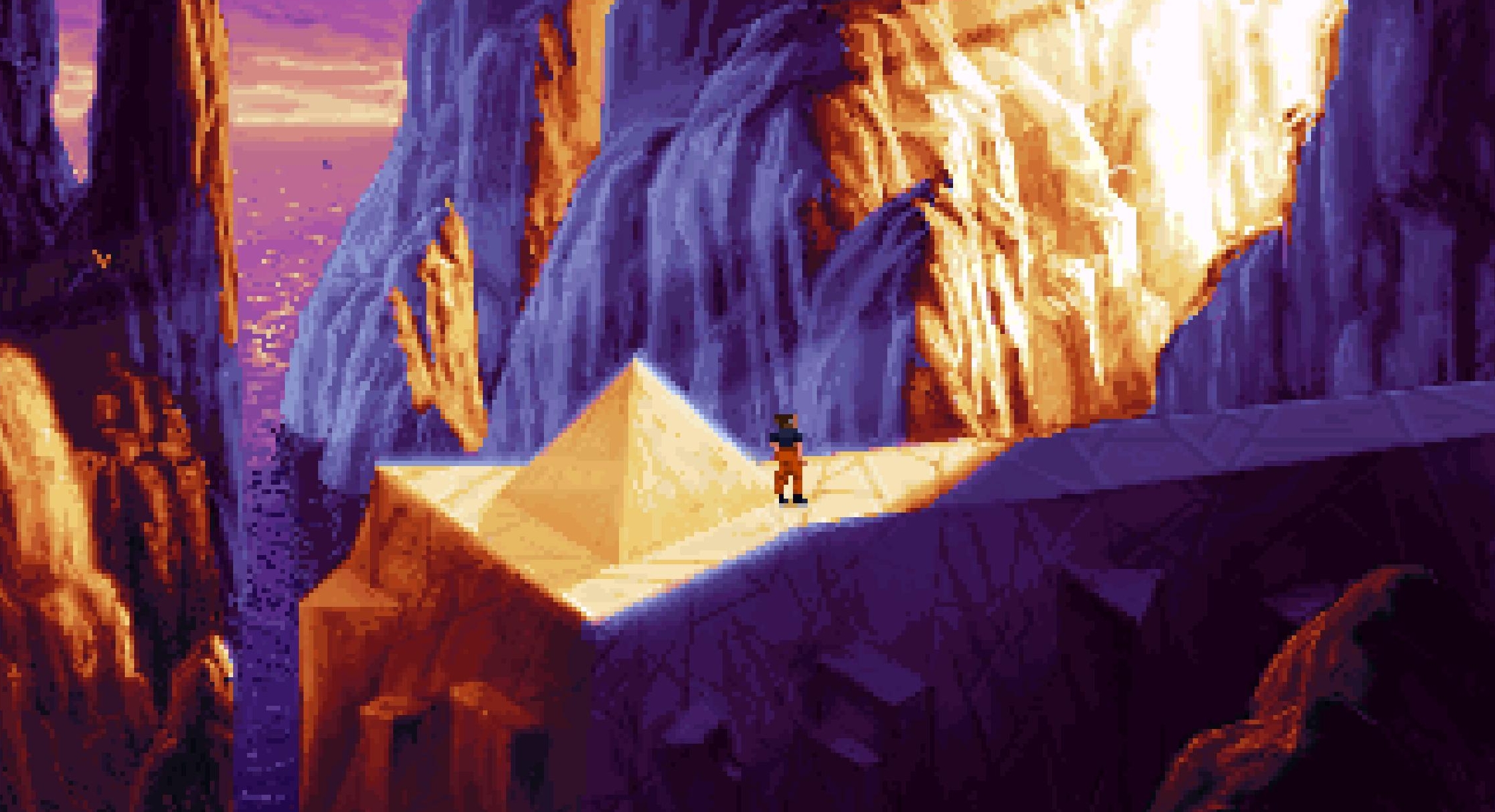

The Dig is, famously, a spare idea of Stephen Spielberg’s. I love how trumped up this is, as if it were about to be a new major motion picture, but then Spielberg though, “Wait! No! The only way for my vision to be truly realised is in point-and-click adventure form!” Rather than the reality - it was a leftover plot from an episode of a TV series that would have been too expensive to film. But it matters not - while the specific plot of The Dig might not be anything groundbreaking or unique, it’s the way it’s realised that makes this game such a favourite for me. The Dig to me is all about a sense of place. A distant remoteness. It’s a beautiful game, it’s packed with some great writing and excellent voice performances, and most of all, it feels wonderfully abstract and unusual. Things start with a giant asteroid hurtling toward Earth. So a rag-tag group of experts are sent up to place charges that will redirect its course into orbit around the planet. (And yes, this came years before Armageddon and Deep Impact.) There’s your character, Commander Boston Low, as generic whitebread a military character as his name makes him sound, yet brought to vivid life by Robert “T-1000” Patrick. Briefly along with him comes old friend and payload specialist Cora Miles, as well as pilot Ken Borden. And for most of the game there’s archeologist/geologist Ludgar Brink, and journalist Maggie Robbins. The five of them begin by trying to stop the end of the world, but very quickly find themselves countless light-years away on a mysterious alien archipelago.

I find it very interesting that at the time of its release, it was considered that LucasArts had taken a huge diversion away from their standard style with this project, with a game that - to quote so many - “had puzzles more like Myst”. Fear not, intrepid friend, it does not. What they mean is, The Dig’s alien world is covered in peculiar alien machinery, and working out how to use it is a large part of what you do. But thankfully, instead of randomly flipping levers and putting your head in your hands at the lack of an even rudimentary understanding of human logic, here it’s much more about what’s an incredibly traditional LucasArts motif: judicious use of inventory items. What’s really different about this is that it isn’t wacky. While LucasArts were one of the very few developers about whom that word could be used not as a pejorative, it’s actually rather lovely to see what their design chops could do when applied to a game that isn’t a comedy first. The Dig is science fiction first, with humour where it belongs within.

It certainly had a difficult development. During its six years it went through a series of project leads, which is rarely a good sign. Yet those leads were a who’s who of LucasArts stars, starting off as a project by The Last Crusade’s Noah Falstein, then a more adult and violent incarnation via Brian Moriarty, then toned down by Dave Grossman. Finally it land with Sean Clark, who had previously been one third of Sam & Max’s creation. One can only imagine what a poisoned chalice it must have felt like by this point, three years late, and with the weight of expectation from Spielberg’s involvement. Yet I really strongly believe it works. The ending doesn’t. We’ll get to that. But as an artistic creation of atmosphere and dissonance, I really think it does. I like that none of the characters is especially likeable. I like that their relationships sour rather than improve. I like that it’s never clear at any point whether you’re doing the right thing by fathoming this abandoned alien tech, or perhaps even something completely disastrous.

Yet this time through, a problematic vein became more apparent to me, rather consolidated by the game’s rushed and ultimately nonsensical ending. It’s Boston Low. He’s like an unaware study in white male privilege. (A lot of spoilers follow.) OH NO! HE SAID THOSE WORDS! ALL IS LOST! And yet, goodness me, how. Boston Low should have been an excellent exploration of how a bolshy, over-confident, under-brained individual needs to learn to stop wise-cracking and start listening to his peers. For so much of the game, it seems it’s going that way. Low makes impulsive decisions that go against the advice of his expert colleagues, and while he keeps getting away with it, it looks as though his comeuppance must be about to arrive at any moment. The relationship with Maggie Robbins is about as ’90s media as it gets, an era where it was impossible to have a man and a women in a situation without their every discussion being flirty pot-shots, obsessively focused on their “battle of the sexes”. Bleaurgh. From the “she gives as good as she gets” school of equality, Robbins is established as subordinate to Low, repeatedly told of her inferiority because of her job, and ultimately gets to live or die based on Low’s whim. The “balance” comes from her being snarky back to him. [Friends theme.] Robbins is far more competent and informed than Low, and for the lengthiest second act of the game she just gets on with her own thing, translating the alien language and actively avoiding interaction where possible. Yet in the game’s final moment, after she’s basically saved the day by understanding how to use the alien devices and implementing them, she joins in the crowing celebration of Low’s victory over adversity. “You did it Boston.” But did what?

What he actually does is defy the warnings of an ancient alien creature, who repeatedly informs him that none of their own species were ever strong enough to survive entering the - hnngggh - Sixth Spacetime, and there’s no way he will either. So when it comes to that final reckoning, that moment of truth, how will Boston survive where no one else ever could? Um, shrug. He just does. Maybe it’s his extraordinary everyman-ness? The inherent power that comes with being a Good Ol’ Boy (TM)? Oh it’s such absolute bilge. And such a shame! Because a game in which Low’s over-confidence was almost his downfall, where he eventually realises he depends upon the shared abilities of his colleagues, would have least made some narrative sense of everything that came before. Rather than a guy who defies every piece of advice he’s ever given in favour of just pressing a big shiny button because it’s there, then getting praised, “No, the credit belongs to you. We once revered a great inventor, because he opened the door to unchanging eternity. But YOU opened the passageway back into true life.” Is he Jesus now?!

Gosh what a lot of complaining. And spoiling. But this is very much the point. Because The Dig is great when it doesn’t yet have its ending. It’s just such a pretty, interesting game to explore, each new scene a masterpiece of pixel art, packed with amazing animations. And the colours! Oh my, the colours. On top of this, there’s a tremendous amount of good writing, big long conversations you don’t usually find in this format, people speaking intelligently to one another, rather than just setting up the next gag. Arguments! How often are there arguments in games? And the music! Michael Land’s score is utterly masterful, whether it’s emboldening dramatic moments, or ambiently tinkering away in the background, always adding an ominous edge to the tale. I also love it for silly reasons. One of my favourite ever TV programmes was the far-too short-lived 2009 show Defying Gravity, a potentially wonderful programme about a group of astronauts following some mysterious alien artefacts on an exploration of our solar system. I loved how unknowable it was in terms of where it was going (and we never did get to know, boo), but I still love to watch it now. The two share so many soft-sci-fi themes, that particularly appeal to me. Calm, gentle stories about exploration and understanding, and the relationship between a fractured crew. (It certainly helps how much Robert Patrick sounds like Defying Gravity’s Ron Livingston.)

The Dig is a game that proves endings can be incredibly unimportant. In fact, I recommend playing right up until the moment Maggie starts the machines, and then just turn it off and imagine your own climax for the storyline, because whatever you come up with will be better than what it offers. Also you could imagine conclusions to the very many fantastic questions and interesting plot ideas it raises along the way, and then completely forgets about at the end. Oh, yes, and some of the puzzles are completely dreadful, and you’ll have a happier better life if you just grab a walkthrough for the awful, AWFUL drone/lens puzzle near the start. But I love it! I’m not sure I’ve done a great job of justifying why at all. Perhaps I simply can’t. Maybe I’m simplistic enough that pretty colours and wonderful music are enough for me, sometimes.

There. No one can be cross with me now, because I’ve said everything that’s wrong with it, and that I love it so much anyway. Apart from Orson Scott Blowhard fans. Or those who want to boycott anything involving Orson Scott Card. Or people who can’t read the word “privilege” without having conniptions. Think I should be good.

Can I still play The Dig? Yes, very easily. As ever, the GOG version is better than the Steam version. GOG has it running through SCUMMVM, so it manages being fullscreen a lot better, and can run nicely in a window too. Should I still play The Dig? Well, if you’re me, yes! It’s a game that makes you feel all happy to be playing, despite its many issues. And gosh, it’s so pretty. If you’re not me, and there’s a good chance you aren’t, then you’ll have to make your own mind up.